On January 31, 1867, the Social, Civil, and Statistical Association of the Colored People of Philadelphia offered the fourth in their 1866-1867 course of lectures at Philadelphia’s National Hall. Tickets cost 35 cents, and could be purchased at the door or in advance from the African Methodist Episcopal Church Bookstore at 631 Pine Street, Trumpler’s Music Store at Seventh and Chestnut, or members of the Association’s Committee of Arrangements, led by William Still and Jacob C. White Sr. The February 2, 1867, Christian Recorder noted “a large audience of both colors” attended.

Listeners that night were deep in the swirl of Reconstruction—as the choice of speakers for the course, from General Oliver O. Howard to Congressman William Darrah Kelly, testified. They might have been wondering whether the state legislature would ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, or they might have been thinking about the ongoing battles over racial discrimination in the city’s transit system. They might have been thinking of the Philadelphia Public Ledger’s New Year’s Day issue, which hoped to see “North and South heartily reconciled and fully one again, politically and socially.” Or they might have been remembering the association’s last event, on January 3, when Frederick Douglass linked African American rights and women’s rights when told a packed house, “Drive no man from the ballot-box because of his color, and keep no woman from it on account of her sex.”

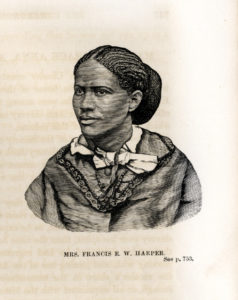

All who came on that chilly Thursday evening, though, wanted to see Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who the January 26, 1867, Christian Recorder promised would “deliver her new and eloquent lecture on ‘National Salvation’” to the citizens of the city she had recently made her home.

No wonder: so accomplished, so lively, and so forceful were her lectures that newspaper coverage regularly compared her positively to white radical sensation Anna Dickinson. A letter in the September 15, 1866, Recorder even said, “We have heard Frederick Douglass, and hesitate not to say that for beauty of expression, richness of illustrations, and, in a word, rhetorical finish, she is his superior. He is more massive than Mrs. H., but she is more polished than he, and fully his equal in warm and glowing eloquence.”

The lecture wasn’t out of the ordinary for Harper. In July 1866, she’d spoken at Philadelphia’s “Freedmen’s Fair” benefit before journeying to lecture in cities ranging from Newark to Washington, D.C. The turn into 1867 found her giving several lectures in Nashville, Tennessee; after her January 31 lecture and a brief respite in Philadelphia, April and May would see her in South Carolina for yet another set of lectures and a speech at a radical Republican state convention.

What makes Harper’s January 31 lecture rare is that we have its full text. The Philadelphia Evening Telegraph printed a transcription of “National Salvation” the day after Harper spoke. That transcription is shared below.

The Telegraph took a “hands-off” approach to the transcription—not only presenting it, uninterrupted, but asserting that “the merits of the lecture which we give below will speak for themselves.” Still, featuring Harper’s lecture—along with a biographical sketch and a separately published poem—was part of a limited opening of the paper’s pages to Black subjects. The Telegraph also shared transcriptions of other lectures in the association’s course—including Douglass’s, published in the January 4, 1867, issue—and offered a massive and somewhat friendly article on Philadelphia’s Black community in their March 30, 1867, issue, curiously titled “Africa! The Colored Population of Philadelphia: Their Numbers, Callings, and Manner of Life.” The condescending tenor of such work can be guessed at from language in the paper’s biographical sketch of Harper: “she is a living and present proof of the fact that the colored race is not hopelessly depraved and benighted.” That pompous, patronizing tone—notably, the Telegraph sometimes supported Andrew Johnson—reminds us of how often we must sift through white noise to find Black voices.

The Telegraph’s transcription of “National Salvation” nonetheless gives an unparalleled sense of Harper’s Reconstruction oratory—oratory that brought her national attention and powerfully supported a new, major phase of her literary career, one led by her serialized Recorder novel Minnie’s Sacrifice (1869) and her powerful long poem Moses: A Story of the Nile (1869). Frances Smith Foster’s groundbreaking collection A Brighter Coming Day: A Frances Ellen Watkins Harper Reader reproduces only two speeches from this period, both presented at events where Harper shared the platform—the brief “We Are All Bound Up Together,” given at the Eleventh Women’s Rights Convention in May 1866, and the slightly longer “The Great Problem to Be Solved,” given at the Centennial Anniversary of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, on April 14, 1875, in Philadelphia. When talking about Harper’s Reconstruction oratory, most scholars rely on these texts or on the brief snippets—presented through both quotation and paraphrase—in press coverage of Harper.

“National Salvation,” however, runs over 5,000 words—more than three times the length of “We Are All Bound Up Together.” Further, only one other figure was noted in event announcements: Philadelphia singer Elizabeth Greenfield, the celebrated “Black Swan,” who regularly gave short performances to round out association events. Harper’s lecture was the raison d’être for the evening’s gathering. As such, “National Salvation” gives us a much fuller example of the content, character, rhythms, and rhetorical strategies of Harper’s oratory.

Harper’s position at the podium that night was one of both experience and rebirth. Born Frances Ellen Watkins in Baltimore in 1825, she’d lectured on abolition and temperance during the 1850s throughout the Northeast (going as far west as Indiana), and she’d published a rich range of literary work—short fiction, essays, letters, and individual poems in periodicals ranging from the Liberator to the Anglo-African Magazine and from the National Anti-Slavery Standard to Frederick Douglass’ Paper, as well as a pamphlet collection, Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, originally published in 1854 and enlarged in 1857, that built in part from her recently rediscovered first collection, the c.1846 Forest Leaves.

But when she married Fenton Harper on November 22, 1860, in Cincinnati, she pulled back from lecturing, published much less, and helped build a family—the Harpers’ daughter Mary joined Fenton Harper’s children from an earlier marriage c.1862—and farm outside Columbus, Ohio. Only with Fenton Harper’s untimely death in May 1864 did she return to lecturing—called by both economic necessity and a recognition of how much the nation-at-war needed her voice.

Those early lectures included a speech to the National Convention of Colored Men held in Syracuse in October 1864 and lectures with titles like “The Mission of the War” and “The Causes and Effects of the War.” Harper was educating audiences from Indianapolis to Philadelphia, in the words of the May 21, 1864 Recorder, about the U.S. government’s “slow awakening” to “the character and influence of slavery and slave-power,” “its final comprehension of the question and magnitude” of the Civil War, and “the future of the nation, conditions of reconstruction, [and] the relation of the blacks to that future.” The centerpiece of these lectures was “an earnest appeal for a national recognition of the colored man as freeman and citizen.”

By early 1867, that appeal had developed into a multi-faceted argument that full civil rights offered the only path to “National Salvation.” Asserting early in that January 31 lecture that “slavery, as an institution, has been overthrown, but slavery, as an idea, still lives in the American Republic,” Harper explores how the forces that broke the nation and caused the Civil War still split the populace. Only “a higher form of republicanism and a purer type of democracy”—ideas she frames in a deeply Afro-Protestant sense of history, “with truth and justice clasping hands”—could “win the fight.”

On one level, Harper’s sense that both slave-power and slavery still lived deeply informs the critique of Andrew Johnson that runs throughout the lecture. In an extended metaphor that received some press coverage after the lecture, she depicts him as an unknowing “great national mustard-plaster” spread “all over this nation, so that he might bring to the surface the poison of slavery which still lingers in the body politic.” But her direct calls to impeach Johnson—to throw away the “plaster” when its work was done—are only a piece of her larger naming of white racism and its tentacles. Harper treats the racist violence at the heart of the 1866 riots in Memphis and New Orleans, like Johnson’s person and policies, as clear extensions of the long history of American politics, “a history of compromise and concessions from the hour that Georgia and South Carolina demanded the slave trade, down to the last Constitutional amendment.”

In her trademark weaving of multiple senses of the domestic, Harper speaks in great depth about the newly freed folks of Kentucky and Tennessee she met touring in 1866, emphasizing their love of liberty and country, their great faith, and their “dignity of soul.” Here, she exhibits an updated version of her antebellum lectures, which Manisha Sinha reminds us “combined abolitionist polemics with literary romanticism.” These people’s stories—and those she heard from diverse other newly freed folks on several wide-ranging visits to the South—touched Harper deeply: they became the subject matter for several poems (especially in her 1872 Sketches of Southern Life) and novels Minnie’s Sacrifice and Iola Leroy (1892).

On that January night in Philadelphia’s National Hall, she told listeners that “some of the most beautiful lessons of faith and trust that I have ever learned, which could never have been learned in the proudest temples of wealth or fashion, I have learned in these lowly homes and cabins of Tennessee.” These recently enslaved people, Harper asserts, had a stronger sense of nation and home than most of the rest of the country. The hands of Andrew Johnson, she tells us, “are not clean enough to touch the hems of their garments.”

Nor, she submits, are the hands of those worrying over the “bugbear” of “social equality” or the hands of white Northerners who do nothing to stop racism at home. In the lecture’s amazing final sections, she says “I am coming right home to Philadelphia” and “am not going to bathe my lips in honey when I speak.” What follows is a stunning crescendo of condemnation—reminiscent of Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”—that depicts representative Philadelphians who allowed a Black woman to be kicked off a city car. Harper, indignant, asserts that “when that man kicked that woman, he kicked me. He kicked my child, and he kicked the wife and child of every colored man in Philadelphia . . . the wife, sister, and child of every colored man who went out to battle and to lay down his life for his country. . . .”

Harper shares that this moment also led to one of her young daughter Mary’s first recognitions of racism, reminding us of Harper’s rhetorical habit of recognizing the political and the public as “domestic,” as threads of lived experience. This powerful linkage also highlights Harper’s integration of tropes of motherhood and widowhood into her self-representation in the wake of the Civil War—rich ground for further study.

This striking content is matched by Harper’s skill with rhetoric, rhythm, and tone. Her seemingly simple and repeated address to the audience—“My friends” is a case in point—draws connections to her audience but also highlights the responsibilities inherent in truly being a “friend.” Harper’s escalation of moral and emotional tone is paired with, alternately, stunning pathos and wicked humor (often biting irony) that temporarily diffuses—but never dismisses—the growing tension. There are moments in the speech—especially after her powerful sequence of images tied to racism surrounding city transit moves into a critique of “social equality” fears—that make us laugh with their unveiling of absurdity, even as we cry and rail against how that absurdity causes immense tragedy within individual Black lives. When we remember, per the Telegraph’s biographical sketch, that she was “rather small,” “with vivacious manners and an enthusiastic bearing” filled with “earnestness and sincerity,” the fireworks at the lecture’s end seem all the more spectacular.

Such moments also remind us that, as we move toward rightfully recognizing Harper as one of the most important American public artist-intellectuals of the nineteenth century, we need to ensure that her oratory is, in turn, a center of our studies.

Editorial note: The February 1, 1867, issue of the Telegraph is available digitally through the Chronicling America project. I share the full Telegraph article, including the paper’s biographical sketch and the brief introduction provided by AME minister James Lynch, in part to give a sense of the event. Beyond this, though, the sketch offers personal information available only from Harper or a close friend like William Still—including some material that complicates existing biographies—and thus functions as a valuable artifact of Harper’s careful self-presentation and reputation-building. The poem referred to in the sketch is Harper’s “Appeal to the American People,” which had been published earlier in the July 21, 1866, Recorder, was collected in Harper’s 1871 Poems, and is reproduced in Brighter Coming Day; as it is widely available and was not a part of the lecture, I have not included it. Of note, Harper gave the lecture—or one with this title—at least once more, as part of the 1866-1867 course of lectures at the Lyceum of Salem, Massachusetts. Original spelling and punctuation has been retained with the exception of one potentially confusing moment when the Telegraph gives “pretroleum” for “petroleum.” Audience responses given in parenthesis in the original have similarly been retained.

***

National Salvation.

A Lecture Delivered Last Evening at National Hall, by Mrs. F. E. W. Harper, with Some Account of the Lecturer.

[Official Report for the Evening Telegraph.]

The fourth lecture in the present course before the Social, Civil, and Statistical Association of the Colored People of Philadelphia, was delivered at National Hall, last evening, by Mrs. Frances E. W. Harper, a colored lady of more than ordinary oratorical powers. In this connection a

Sketch of Mrs. Harper

may not be uninteresting. Her early life, under the name of Frances Ellen Watkins, was passed in Baltimore, where she was born in 1825. Her mother was born a slave, but through the exertions of her grandmother her freedom was purchased, and Miss Watkins was, therefore, free from birth. She remained at school in her native city until she was fourteen years of age, and subsequently to that obtained her own livelihood for some years by sewing and teaching school. In the former occupation she was for some time employed by Mrs. Isaac Cruise, of Baltimore. This lady was the possessor of quite a large library, to which Miss Watkins had free access at all times. Being strictly enjoined against perusing novels, the information which she thus picked up in her leisure hours was of the most solid and desirable character. Her experience as a school teacher was quite extensive, and this calling she followed at times in Baltimore and the neighboring country for some years.

Miss Watkins was early given to poetizing, some of the productions of her muse—of which a specimen, entitled “An Appeal to the American People,” is printed elsewhere in our issue of to-day—exhibiting more than ordinary depth of thought and fervor of expression. These early poems she usually composed while busy with needle and thread. While on a visit to New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1854, she recited some of her poems to her friends, who were so deeply impressed with their merit that she was invited by them to appear before the public as a lecturer. Just previous to this she had become strongly imbued with a desire to contribute, in some measure, to the enlightenment and social elevation of the outlawed race to which she belonged. This ambition sprung from the recital in her presence of a story which in those days was as common as it was disgraceful to the community by which it was tolerated. A free colored man had moved into the State of Maryland, and in pursuance of the law then and there in vogue, he was for this dire offense seized by the authorities and sold into slavery. Being afterwards taken to Macon, Georgia, he there made his escape, but only to be recaptured and returned to a bondage from which he was soon after released by death. From the time that Miss Watkins listened to this oft-repeated tale, she resolved to devote all her time and energies to the welfare of her kindred race. So she was nothing loth to appear upon the platform, and delivered her first lecture in New Bedford in 1854, from which time forth, for six years, she continued upon the stage, restricting her labors principally to the New England States. For a time, however, she acted as an agent of the Anti-Slavery Society in this State.

In November, 1860, Miss Watkins was married in Cincinnati to Mr. Fenton Harper, a free colored man, from Loudon county, Virginia. Her married life was passed on a farm in the neighborhood of Columbus, Ohio. During this time she seldom appeared in public as a lecturer.

Mr. Harper died in May, 1864, and in October, 1865, Mrs. Harper resumed her former calling, which she has steadily pursued up to the present time. New England was again her favorite field, but she has likewise spoken in many of the other States, and, during the present winter, has passed some time in Kentucky and Tennessee, addressing the people, white and black, whenever and wherever she could get a chance. On the 24th of last month she spoke at a meeting in the Capitol, at Nashville, Tennessee, her oratory even receiving praise from the semi-Rebel sheets which still flourish there, although her politics were denounced as abominable and as tending to create a hatred between the races, deeper than that which at present exists. Last evening was the occasion of her third appearance before a Philadelphia audience.

We have given this lengthy sketch of Mrs. Harper’s career, because she is a living and present proof of the fact that the colored race is not hopelessly depraved and benighted. In person she is rather small, and of prepossessing appearance, with vivacious manners and an enthusiastic bearing that impresses all who listen to her, either in public or in private, with her thorough earnestness and sincerity. The merits of the lecture which we give below will speak for themselves. She was introduced last evening to the audience by the following

Remarks by Rev. Mr. Lynch,

Ladies and Gentlemen:—You are assembled to listen to one of the most cultivated daughters of the persecuted race, who has plead their cause for more than twelve years, in poetry, in thrilling eloquence, and in logic, from the platform. Additional interest may be expected in this lecture to-night, as she is recently from the South, where she lectured to the delight and instruction of the loyal whites and blacks; and, judging from the encomiums of semi-Rebel Andrew Johnson journals, we have discovered that she possesses a power that we have not before known—that of enchanting a certain kind of serpent called Copperheads. I now have the honor of introducing to you Mrs. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. (Applause.)

Address of Mrs. F. E. W. Harper,

Reform has her seed-time and her harvest, her night of trial and endeavor, as well as her day of success and victory. But before her ears are greeted with the shouts of triumph, they are hailed with the hisses of malice and the threats of revenge; but as amid the darkness and the cold, nature spreads her dews and carries on the work, so amid the darkness, cold, and pain the spirit of reform carries on her work of progress, and sows in tears the harvest she is to reap in joy. Men tread with bleeding feet their paths, and from the soil covered with the ashes of martyrs and drenched with the blood of heroes, has sprung up a new growth of character and civilization.

Now in the question of dynamics, or the application of force to any end, it is necessary to know the amount of resistance to be met, and the power which is needed to overcome that resistance. For instance, a man who would wish his locomotive to go fifty miles an hour would not be acting very wisely if he only put on steam enough to carry it ten miles an hour; and the same remark would apply to the man who would wish a large water-wheel turned by little rills, and would supply fifty gallons of water where a thousand were needed. This man would not be acting wisely in these particulars. He would be failing to take the right means to gain the desired end.

Now, in the moral and political world, as well as in the physical, there are resistances to be met and obstacles to be overcome in carrying out the aim of true civilization, which is the social advancement and the individual development of the human race. And if we look through the history of the past, we will find that there has been an old struggle going on for ages—a struggle of the oppressed against the oppressor—a battle which has been fought under different names, and continued under different auspices, but which is still the continuation of the old struggle.

In one age it has assumed the form of a conflict between the lowest of the people and the hierarchy; still again against the despotisms which shackled the human intellect and put fetters upon the human conscience. In another age it has been a struggle between freedom on one side and slavery on the other. Slavery, not content with having simply a battle of ideas, resorted to the arbitrament of the sword, and the sword decided against it, and slavery went down in tears, and wrath, and blood—went down amid the rejoicing of men and women who had burst their chains.

Now slavery, as an institution, has been overthrown, but slavery, as an idea, still lives in the American Republic, and the problem and the duty of the present hour is this:—Whether there is strength enough, wisdom enough, and virtue enough in our American nation to lift it out of trouble; whether by its legislation and jurisprudence these distinctions between man and man, on account of his race, color, or descent, shall cease. Last year, my friends, I spoke of the nation’s great opportunity. I still think we have one of the greatest opportunities, one of the sublimest chances that God ever put into the hands of a nation or people.

But it is not in opportunities presented, but in opportunities accepted, that the very pith and the core of our national existence lies. What we need, my friends, in this county, is all the energy, all the wisdom of the nation so to reconstruct this Government that it will render another such war impossible. There is something wonderful, my friends, in the power of an idea. And what to-day is the watchword of the present hour? It is the brotherhood of man amid the din and strife of battle, amid the conflict of the present age; and yet it is an idea which has been struggling through the centuries, baptized in blood and drenched in tears.

To-day the tendency of the spirit of the age is towards a higher form of republicanism and a purer type of democracy, and yet this idea has been struggling for ages. I look away back on the pages of history, and hear it preached by Him who made it, in His death, the sublime lesson of His life eighteen hundred years ago.

Proud and imperial Rome stood crowned and sceptred amid her seven hills, apparently the strongest power in the world. At the same time, in a manger lay a child whose work of reform was destined to live when the proud empire should be laid away amid the dead kingdoms. This idea, my friends, met with opposition, just the same as this idea of equal rights meets with opposition to-day. This man held up the single idea taught by Jesus Christ, with His giant enthusiasm for humanity, and it was met with opposition from every distinct class.

And yet this reform, meeting with all this opposition, lived on until it became the professed faith of the most enlightened and progressive nation on earth. The men who martyred Jesus Christ now sleep in forgotten graves. He lives and shines in the hearts of all who accept Him as the true and living Christ. The crown of thorns has changed to a diadem of glory, and the cross has become a power and ensign of victory.

The Protestant Reformation sprang from the same spirit, and still fights its way against the ignorance and superstition of ages. It lived on until the Inquisition ceased to claim its victims, until the auto-de-fe no longer lit its fires, until Protestant kings sat upon the very thrones from which the edicts against the children of Reformation had gone forth.

Men then grappled with agony and death, so that they could secure the rights which we this day enjoy. We are carrying on the cause, but we have only got through one part of the struggle; the reform we are now carrying on, we may feel assured, notwithstanding all the opposition, notwithstanding all the obstacles in its way, with truth and justice clasping hands, shall yet win the fight.

Oh, my friends, the work goes bravely on! I look back seven years ago, and see this nation apparently in a prosperous career, with slavery bound to her with a four-fold cord. In your commercial interests, men said, virtually, Let us make money, though we coin it from blood and extract it from tears. Here were ecclesiastical interests, the same from Maine to California; here were our political parties clasping hands North and South; and yet they were all snapped asunder, simply because they lacked the cohesion of justice. (Cheers.) Now to-night the question arises, What shall be done? How shall we serve the interest of freedom so that this nation shall be wise enough to know its citizens, and knowing them shall be strong enough to protect them?

One thing that this nation has been doing, is throwing away an element of strength. The colored man, as a laboring force, as a political force, and even as a moral force, in this country is an element of strength or of weakness. As a passive force he is an element of weakness; that is, he weakens the country when he is pressed down in the scale of life, when he is wronged and robbed. But justice will certainly take sides with this people who have been pressed down in the scale of life—a people who are struggling for a higher and purer state of existence. Now, I hold that the colored man is capable of being an element of strength to the American nation.

I have lately been down amid the cabins and humble homes of Tennessee; and—would you believe it, my friends? some of the most beautiful lessons of faith and trust that I have ever learned, which could never have been learned in the proudest temples of wealth or fashion, I have learned in these lowly homes and cabins of Tennessee. There may be some people who think within themselves that it is a little strange Andrew Johnson, after having promised the colored people that he would be their Moses, should turn around, and instead of helping them to freedom, should clasp hands with the Rebels and traitors of the country. (Cheers.)

My friends, since I have come from Tennessee, I am not surprised at the position that Andrew Johnson takes. Do you know why it was that David was not permitted to build the temple of the Lord? Because his hands were not clean; he was a man unfit for the work. And so, when I have gone among some of the people of Tennessee, who have breathed their words of faith and trust, I see in Andrew Johnson a man whose hands are not clean enough to touch the hems of their garments. (Cheers.)

Do you ask me to-night what are the colored people doing in Tennessee? They are doing just exactly what Mr. Lincoln said the colored man might be required to do in this country. They are helping to keep the jewel of liberty in the family of nations. And how are they doing it? I have heard, my friends, of serfs to whom a broader and higher freedom came, and they did not know how to appreciate it, and offered to go back again into serfdom.

I have been in humble homes where poverty has been staring them in the face, and said to them, Would you not rather go back again into slavery? And such an answer as this has come up:—“I would rather live in a corn-crib.” I remember, some few years ago, I met in Louisville, Kentucky, a woman who lived in a room which looked as though it might have been a stable converted into a dwelling. I said to her:—“If your master would take good care of you, would you not rather be back again?” The woman, with eyes filled with indignation, for she did not know that I loved freedom so well that I liked to hear its praise from the humblest lips, said to me:—“Don’t you wish to be free and stamp your foot in Jubilee? God bless the poverty that brings me that privilege.” (Applause.)

There is one thing that has impressed me more forcibly, perhaps, than anything else about the inner life of these people who have lately come up to freedom, and that is their faith and trust in God. I met a mother there who had lost her child. But here was a mother looking over the track of distant years. How did she feel, as a mother who has given her child up to death, saying:—

“That innocent is mine;

I cannot spare him from my arms,

To lay him, Death, in thine.

“I am a mother dear;

I gave that darling birth;

I cannot bear its lifeless limbs

Should moulder in the earth.”

—when her child was taken from her, and when she felt the distance increasing between them, and knew she could not meet it till she met it in another world.

Oh, when I look at this beautiful faith and trust, when I see them, too, in their humble homes, and ask them what has sustained them, what has kept them up in these dark and gloomy years?—the almost invariable answer that comes to me is:—“The power of God!”

I met with a woman in Tennessee who had been the mother, I think she said, of five children. All were absent from her except one. I don’t know that she could say in what part of the world her children were. She prayed for them, and said, “I only see them in my dreams.” This was a woman upon whose heart the shadow of slavery still hung black and heavy. Her husband heard that his children wanted to see him, and he started to go to them; and then word came to this mother and wife that her husband was dead.

Before he started he had contracted a debt of twenty-five dollars. When the news came to the mother of his death, what did that woman do? She went and paid off the obligation, by working at nine dollars a week, and living in a house where she was charged five dollars a month. Look at the dignity of soul in that woman! Her husband dead, no one could have forced her to pay that debt; yet with such a keen sense of honor and dignity of soul, she takes up the obligation, and pays it off. Interested friends, let me tell you Andrew Johnson’s hands were not clean enough to clasp that woman’s hands, to be her Moses, and lead her up to freedom.

When I see this faith and trust, it is beautiful. But there is another feature of life among these people which might impress you just as pleasantly, and that is the tender humanity displayed among them. I have gone into the little cabins, where the light of the sun came through a single window without a pane of glass, and yet, in that humble home, they were taking the children and sending them to school, and it is a thing you will often see in many of these little homes. This people, that have gone through this weary night of suffering, have come out of it with a tender humanity, clasping in their arms poor little orphan waifs, giving them shelter, schooling, and a home. (Cheers)

And then there is another feature, and that is their greediness for knowledge. A few weeks since I was in Louisville, Kentucky. They had just opened a school for colored people, charging twenty-five cents a month, I believe. The people were so eager that their children should have schooling, that by half past nine o’clock it was necessary for the Superintendent to lock the door, because they were overcrowded with applicants, and many of the parents went away in tears because their children could not enter the school. This greediness for knowledge on the part of the colored man is an element of hope and future strength in this Government. (Applause.)

The ancients had an idea that there was a giant chained under Mount Etna, and that the eruptions of the mountain were caused by his turning over. So when I go down South, and see and hear of their eagerness for knowledge, I see the rising brain of the colored man, and I hope, my friends, that if any of the enemies of humanity shall attempt to build any system of despotism with an idea to the disenfranchising of a race—making it in the name of freedom, and torturing it with the essence of slavery—that the rising brain of the colored man will be evoked, and quell the despotism at the start.

In treating this question, I think of the legend of ancient Rome, of the chasm that yawned there, and of which the sorcerers predicted that whosoever should bring the most precious gift should be the means of closing it and saving the city. Cassius, thinking that he himself was the most precious gift, leaned into its yawning jaws. The legend has been repeated in part in this country. Slavery has made a chasm in our American republic. It has made you two people in the midst of one nation—a people for freedom and a people for slavery—a people for knowledge and a people for ignorance! And what have you tried to do? You have been trying to bridge it over by compromise, until the history of American politics is the history of compromise and concessions, from the hour that Georgia and South Carolina demanded the slave trade, down to the last Constitutional amendment.

Slavery wanted more room, and you gave it land enough for an empire. It wanted the power to hunt the trembling fugitive, and the Fugitive Slave bill was passed, and the trembling victim was thrown into the chasm. Still it yawned, and slavery was not satisfied. For itself it wanted a white man’s government, and you made a trial of a white man’s government in this country for four years, and the prayers of the freedmen are ascending that we may never have another such a government as long as the world may stand. (Applause.) You threw into this chasm a few million lives, warm with the rich blood of your patriots. You threw into it the life of your loving, honored chief—Abraham Lincoln. (Applause.) And yet to-night the chasm yawns. You are still two people in the midst of one nation.

Would you close over this chasm? Do not try any more compromise or concession; you might as well try to bridge with egg-shells the Potomac river. What you need to-night is to take the shackle from the wrist of the colored man, and to put the ballot in its stead. (Applause) When I see the streets of New Orleans and Memphis red with the blood of unexpiated murders, and I hear of that miserable Recorder counselling them to burn and hang the nigger, I ask that the colored man should have that much power in his hands, to turn all such men out of office. (Applause.)

Look at New Orleans. Whose fault was it? You should ask that of Andrew Johnson. Let me tell you Andrew Johnson is not the most guilty man in this republic. I don’t know but that we have needed him. I have, in the course of my life, had to put a mustard plaster on myself. Now, I don’t like a mustard-plaster, and yet I would rather suffer an hour with it than suffer a pain in my chest for a week. I don’t know but what we have needed Andrew Johnson in this country as a great national mustard-plaster, to spread himself all over this nation, so that he might bring to the surface the poison of slavery which still lingers in the body politic. But when you have done with the mustard-plaster, what do you do with it? Do you hug it to your bosom, and say it is such a precious thing that you cannot put it away? Rather, when you have done with it, you throw it aside.

Now, my friends, why do you not do the same with Andrew Johnson, and impeach him (applause), and bring him before the bar of the nation, and prove to the world that this American nation is so strong, and so powerful, and so wise, that the humblest servant beneath its care, or the strongest, is not to behave without its restraint.

I was in Boston a few days since, and I heard a gentleman speaking of an accident that had happened. It was of an engineer who was insane. I suppose that the people did not know that he was insane. He got on the locomotive, and he imagined that he was going to the moon. He was not swinging around the circle, but was going to the moon, and he was dashing away wildly. Death was of no moment to him; he was going to the moon. Now what did the people do? Did the people stop to ask his friends about him, or try him a little longer until he had done some mischief? No, no; the case was too imminent for that. A student picked up a block of wood to try to dash him off. So to-day Andrew Johnson stands at the head of the Government, a man who is striking hands with the Rebels of the South. Is there not in this nation, from the Potomac to the Rio Grande, a hand strong enough and earnest enough to throw at him the billet of impeachment, and let him go home to Tennessee to rust out the remainder of his life? (Applause.)

I don’t, my friends, berate him because he may have swung around the circle from the seaboard to the Mississippi, although, as far as that is concerned, it reminds me that the colored man has the advantage of him there. I remember when I was a girl how the colored man used to be burlesqued in popular songs. One of those songs ran thus:—

“If I was President of the United States,

I would lick molasses candy and swing upon the

gates.”

That might have been a burlesque upon the colored people; but, my friends, I have lived to see the time when the President, though he don’t swing upon the gates, does swing around the circle, and though he does not lick molasses candy, takes something that is a great deal stronger. (Sensation.)

Now, this reform must be carried on, as others are, against opposition and persecution. This cause has already passed through part of the time of persecution. It is a different thing to-day from what it was when William Lloyd Garrison threw his words like burning coals upon the nation’s heart. Since then the ideas that originated in the Boston garret have become a mighty building, bearing upon its bosom hundreds of millions of men, women, and children, translating them from the oligarchy of slavery to the commonwealth of freedom. Still the work needs courage to-day.

There is a small matter of prejudice that I want to take up—that against color in particular—and I am coming right home to Philadelphia, and not intending to spend my ammunition on the Rebels, who are so many thousand miles away. But I am to talk to those who clasp hands with Rebels in the city of Philadelphia, and I am not going to bathe my lips in honey when I speak. Two weeks last Saturday night I was in Louisville, Kentucky. I came on from Nashville, had a little business down the street, and I got into the city cars; and I found that there is no difference there in Kentucky as to the people’s riding in the cars; Kentucky had just burst from her chains, yet she was ahead of Philadelphia in that.

I went into the house and picked up a Philadelphia paper—a Christian Recorder. What did I read? There I read that a woman had been kicked out of the cars in the streets of this city. What had she done? Simply claimed her right to travel, and had been brutally kicked in these streets. Where was she kicked? Let me tell you. Did you see that man with the surplice, chanting his solemn litany? That man is an Episcopalian minister, and that brutal man kicked her in his presence.

Did you see that man with a simple ritual? He is a Presbyterian. I don’t think there is a Church in the world to whom civil liberty owes more than to the Presbyterian Church. They came out and preserved civil liberty in the wilds of Scotland, and this man kicked this woman in his presence.

Do you see that man who has just been celebrating the centenary of his Church, of which John Wesley is the St. Paul? That man is a Methodist, and he kicked her in his presence. Do you see that lady and gentleman, in plain garb? They, too, have a grand memory, reaching away back to William Penn, who came here to Pennsylvania, and taught the world how peace and justice could clasp hands; and Mary Dyer, who gave up her life on Boston Common and who died for a principle. (Cheers.) He is a Friend, and that woman was kicked in his presence.

Do you see that man, upon another plain, who knows it is better to have the peace of Christ than to quarrel about Christianity? He is a Unitarian; kicked in his presence also. Do you see that man, who believes in God and the brotherhood of the human race, and that He will ultimately clasp us all in a living embrace? That man kicked her in the presence of the whole popular Church of Philadelphia, and I ask them have they done their duty on this subject?

I pick up the papers, and I hear a great deal said about the running of the cars on Sunday. The day is sacred in Philadelphia, but man is vile. Where did he kick this woman? In the very streets over which colored men marched to the front, faithful to the country when others were faithless (applause)—who were rallying around the flag when Rebels were trampling it under feet; true to the country when she wanted a friend. Witness, now, that the sisters and mothers of these men can be kicked from the cars in our popular thoroughfares. (Applause.)

Friends, when that man kicked that woman, he kicked me. He kicked my child, and he kicked the wife and child of every colored man in Philadelphia. He kicked the wife, sister, and child of every colored man who went out to battle and to lay down his life for his country; and I am here to-night to protest against it. (Applause.)

Last summer I was here; it may have been the fourth of July; it does not matter, though. I was going up the street with my child, between five and six years of age. My friend Mr. Still was with me. He, living on Fifth street, thought the drivers would know him, and wait for us. I did not ask these drivers to take me in; I shall faint upon your paved streets before I ask such a favor. Do you think they would stop for us? Oh, no! They swept by us as if we were paupers.

The next day my child came to me and said: “I know why we can’t ride in the cars; because we are colored!” No women feel this deprivation so keenly as we do, and when my orphan child came home and told me that she had read the cruel, bitter lesson, I felt bad. And yet to-night, poor, ignorant, and trodden under foot as our people are, I would not change souls with the richest and proudest stockholder in Philadelphia. I would not change souls with a man who reproaches his God by despising His poor! (Applause.) Again, my friends, I do not feel that the colored people need despair; we only take our turn in the suffering world.

I do not demand social equality; I do not demand that you shall take us into your parlors, and make us companions of your wives and daughters, if they have no liking for us. All I ask is that you take your prejudices out of the way and give the colored man a chance to grow; give him a chance at the ballot-box. Why this idea of social equality? I don’t know of any colored man that demands it. After all, this thing depends upon social affinities, customs, wealth, and habit, and in some cases on shoddy and petroleum. But there is a dread of blood degeneration.

Somehow I do not think I should like to stand before the world, with pale lips, dreading the bugbear of social equality; afraid of giving the colored man a chance, for fear that he might somehow outstrip me in the race of life. (Applause.) If I was in his place I would say, “I will give him all the chance I can; I will not press him down in the scale of life.” I should feel that I was superior, because of a superior teaching. Look at slavery: has it not robbed us of our wives, children, and husbands; robbed us of our very complexion, and put some of the meanest kind of white blood in our veins? (Cheers.) And we have lived through it all, and come out of the war the very best characters down South. If we don’t complain about it, what right has anybody else to do so? (Cheers.)

O friends! if there is any danger, you make your President and Congressmen; you make your own laws; if any man feels that the case is urgent, let him go before the Legislature and say to them:—“Honorable Sirs—We have a deep concern on our minds; it haunts us by day and comes over our dreams by night. We are so afraid that some colored man’s uncle’s aunt will marry some white man’s cousin’s aunt, and we want you to put a law upon the statute books that no white man shall marry a black woman unless he wants to.” (Great laughter.) I think that they must necessarily be guided by their wishes. Some men have no other wants than those which are low and grovelling; they are like the men to whom the grasshopper is a burden; they are afraid of that which is high.

Justice is high, and liberty is high, and equal rights are high; and these men are afraid of that which is high, and putting their ears to the ground they hear the advancing tread of the negro, and would retard his coming. (Cheers.) Why you have a paper in this city called the Age. The better name for it would be to call it Behind the Age. Last spring it had a call for a Democratic meeting, and in the call it included all those who voted for a white man’s Government. I have been taught that the power of gravity gravitates in the strongest hands. What possibility is there that we should get to the head of the Government, or that the white race should stand trembling before us, or that eight thousand persons are going to get the upper hand of the nation?

He has dropped the rags of the plantation and put on the uniform of the nation. In the District of Columbia he has exchanged the fetters on his wrists for the ballot in his right hand. Mr. Johnson did not admire that very much, so he gave us a veto; he paid us a compliment, somehow, by supposing that we would come into the District for the purpose of giving a vote. If it is such a privilege to an American citizen, he will go where he can have the rights of a citizen.

The colored man is taxed in this country, he is drafted in war; and yet to-night I live in an American republic; I am a taxpayer. The Government may increase its taxes until it runs down every seam and fold of my dress, may tax the very bread I break to my orphan child; but it brings me back a rich compensation when it makes my child free in South Carolina, in Tennessee, and Alabama, and even in this city of Philadelphia when I want to ride in your cars.

Friends, this is the nation’s hour for every heart and hand to build on justice as a rock, to trust in the truth, and never yield. With truth and justice clasping hands, we yet shall win the fight.

***

Further Reading

Manisha Sinha’s quote comes from her fine essay “The Other Frances Ellen Watkins Harper,” Common-place 16:2 (winter 2016).

Any student of Harper’s life and work should start with A Brighter Coming Day: A Frances Ellen Watkins Harper Reader (New York, 1990), edited with an introduction by Frances Smith Foster. Foster’s edited Minnie’s Sacrifice, Sowing and Reaping, Trial and Triumph: Three Rediscovered Novels by Frances E. W. Harper (Boston, 1994) and the sections on Harper in William Still’s The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia, 1872) are also essential. Useful complements to this work include Melba Boyd’s Discarded Legacy: Politics and Poetics in the Life of Frances E.W. Harper 1825-1911 (Detroit, 1994); Maryemma Graham’s Complete Poems of Frances E.W. Harper (New York, 1988); Carla Peterson’s “Literary Transnationalism and Diasporic History: Frances Watkins Harper’s ‘Fancy Sketches,’ 1859-1860,” Women’s Rights and Transatlantic Antislavery in the Era of Emancipation, eds. Kathryn Kish Sklar and James Brewer Stewart (New Haven, 2007), 189-208; and Margaret Washington’s “Frances Ellen Watkins: Family Legacy and Antebellum Activism,” Journal of African American History 100:1 (winter 2015): 59-86.

Recent rediscoveries that broaden this base include Johanna Ortner’s immensely important “Lost No More: Recovering Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s Forest Leaves,” Common-place 15:4 (summer 2015) and my “Sowing and Reaping: A ‘New’ Chapter from Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s Second Novel,” Common-place 13:1 (October 2012). Among exciting recent work on Harper, see Meredith McGill’s “Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and the Circuits of Abolitionist Poetry,” Early African American Print Culture, ed. Lara Langer Cohen and Jordan Alexander Stein (Philadelphia, 2012): 53-74, and Stephanie Farrar’s “Maternity and Black Women’s Citizenship in Frances Watkins Harper’s Early Poetry and Late Prose,” MELUS 40:1 (spring 2015): 52-75.

Carla Peterson’s “Doers of the Word”: African American Women Speakers and Writers in the North, 1830-1880 (New York, 1995) offers the richest primer on Black women lecturers including Harper; Shirley Wilson Logan’s “We Are Coming”: The Persuasive Discourse of Nineteenth-Century Black Women (Carbondale, 1999) offers another good starting point. On the nexus of race, gender, and politics Harper engaged, see Martha S. Jones’s “All Bound Up Together”: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900 (Chapel Hill, 2009) and Carol Faulkner’s Women’s Radical Reconstruction: The Freedmen’s Aid Movement (Philadelphia, 2003). Andrew Diemer’s “Reconstructing Philadelphia: African Americans and Politics in the Post-Civil War North,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 133:1 (January 2009): 29-58 provides valuable local context. Primary sources tied to Black oratory can be found in Philip S. Foner and Robert Branham’s Lift Every Voice: African American Oratory, 1787-1901 (Tuscaloosa, 1997) and the online Colored Conventions Project. Outside of the Telegraph piece, the fullest reporting I’ve located on this specific lecture appears in “Philadelphia Correspondence,” National Anti-Slavery Standard (9 February 1867).

This article originally appeared in issue 17.4 (Summer, 2017).

Eric Gardner is professor of English at Saginaw Valley State University and the author or editor of five books, most recently Black Print Unbound: The Christian Recorder, African American Literature, and Periodical Culture (2015). Two-time winner of the Research Society for American Periodicals Book Prize, he helped found the “Just Teach One: Early African American Print” project, and he blogs at blackprintculture.com.